- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Finding Tessa

Finding Tessa Damascus Station

Damascus Station Charlotte Boyett-Compo- WIND VERSE- Hunger's Harmattan

Charlotte Boyett-Compo- WIND VERSE- Hunger's Harmattan ted klein

ted klein Raspberry Tart Terror (Murder in the Mix Book 30)

Raspberry Tart Terror (Murder in the Mix Book 30) i f6c06dd9cf3fe221

i f6c06dd9cf3fe221 The Five Wounds

The Five Wounds Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom's Cabin

Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom's Cabin The Sociology of Harry Potter: 22 Enchanting Essays on the Wizarding World

The Sociology of Harry Potter: 22 Enchanting Essays on the Wizarding World Kate Williams

Kate Williams Hives Heroism by Benjamin Medrano (z-lib.org)

Hives Heroism by Benjamin Medrano (z-lib.org) Sutton_Jean_Sutton_Jeff_-_Lord_Of_The_Stars

Sutton_Jean_Sutton_Jeff_-_Lord_Of_The_Stars William Deresiewicz

William Deresiewicz Floaters

Floaters The Dragon Chronicles Solana COMPLETE

The Dragon Chronicles Solana COMPLETE Flight of the Diamond Smugglers

Flight of the Diamond Smugglers Advanced Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Operations

Advanced Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Operations Saving Grace

Saving Grace The Darkest Summer

The Darkest Summer The Mirror of My Heart

The Mirror of My Heart Crisis of Faith by Benjamin Medrano (z-lib.org)

Crisis of Faith by Benjamin Medrano (z-lib.org) Pure Blood: Rise of the Alpha

Pure Blood: Rise of the Alpha The Red Thread

The Red Thread Jane Feather - Charade

Jane Feather - Charade The Shut Mouth Society (The Best Thrillers Book 1)

The Shut Mouth Society (The Best Thrillers Book 1) Fork It Over The Intrepid Adventures of a Professional Eater-Mantesh

Fork It Over The Intrepid Adventures of a Professional Eater-Mantesh Wild, Hungry Hearts

Wild, Hungry Hearts Majestic

Majestic Already Among Us

Already Among Us Desmond Young - Rommel, The Desert Fox

Desmond Young - Rommel, The Desert Fox Hooked

Hooked 9781618853158SpecialKindofWomanBergman

9781618853158SpecialKindofWomanBergman Nate (A Texas Jacks Novel)

Nate (A Texas Jacks Novel) Sword and Sorceress 28

Sword and Sorceress 28 Moon Tiger

Moon Tiger The Hailey Young Diaries - 7 Years, 7 Real Stories - (3 of 7 adding wkly): Real stories from the past 7 years, living, loving, and exploring the wild side with a married couple. - One a year

The Hailey Young Diaries - 7 Years, 7 Real Stories - (3 of 7 adding wkly): Real stories from the past 7 years, living, loving, and exploring the wild side with a married couple. - One a year Tales of the Greek Heroes

Tales of the Greek Heroes Coupling Two More Filthy Erotica for Couples

Coupling Two More Filthy Erotica for Couples 2012-07-Misery's Mirror

2012-07-Misery's Mirror Fade to Black

Fade to Black Alef Science Fiction Magazine 006

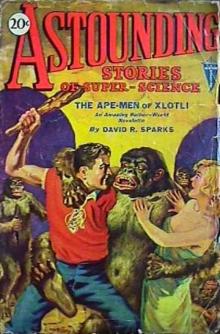

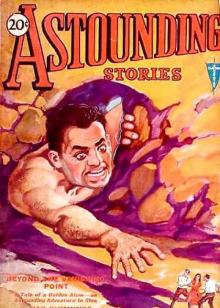

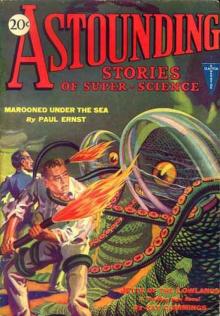

Alef Science Fiction Magazine 006 December 1930

December 1930 Krunzle the Quick

Krunzle the Quick Don’t tell the Boss

Don’t tell the Boss An Involuntary Spark

An Involuntary Spark Meg Xuemei X - ANGEL’S FURY (THE EMPRESS OF MYSTH #5) | Aug 2016

Meg Xuemei X - ANGEL’S FURY (THE EMPRESS OF MYSTH #5) | Aug 2016 Viper

Viper EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) bb-139_mother_gets_a_whipping_nathan_silvers_1988

bb-139_mother_gets_a_whipping_nathan_silvers_1988 Frightmares: A Fistful of Flash Fiction Horror

Frightmares: A Fistful of Flash Fiction Horror Jam

Jam Witch Finder

Witch Finder June 1930

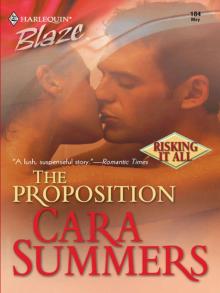

June 1930 B01M7O5JG6 EBOK

B01M7O5JG6 EBOK Until There Was You

Until There Was You UrgentCare

UrgentCare Immortal of My Heart

Immortal of My Heart Great Ghost Stories

Great Ghost Stories Joan D Vinge - Lost in Space

Joan D Vinge - Lost in Space Someone Like Me

Someone Like Me HowToLoseABiker

HowToLoseABiker![[anthology] Darrell Schweitzer (ed) - Cthulhu's Reign Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/anthology_darrell_schweitzer_ed_-_cthulhus_reign_preview.jpg) [anthology] Darrell Schweitzer (ed) - Cthulhu's Reign

[anthology] Darrell Schweitzer (ed) - Cthulhu's Reign Witchin' Stix - Lissa Matthews

Witchin' Stix - Lissa Matthews Plow and Sword

Plow and Sword Ravenous (Lake City Stories .5)

Ravenous (Lake City Stories .5) The Thief

The Thief Afterlife-Isabellakruger

Afterlife-Isabellakruger The Dream Canvas

The Dream Canvas Anything She Wants

Anything She Wants eBook Short Story Competition Runners up

eBook Short Story Competition Runners up Escape Velocity: The Anthology

Escape Velocity: The Anthology![[Burnett W R] Round Trip(Book4You) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/burnett_w_r_round_tripbook4you_preview.jpg) [Burnett W R] Round Trip(Book4You)

[Burnett W R] Round Trip(Book4You) 1-Chloe-Kate-Bella

1-Chloe-Kate-Bella Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair The Troubles

The Troubles Complicit

Complicit Elusive Isabel, by Jacques Futrelle

Elusive Isabel, by Jacques Futrelle A Man of Means

A Man of Means The_Sword_of_Gideon

The_Sword_of_Gideon B00IZ66CZ8 EBOK

B00IZ66CZ8 EBOK If You Give a Duke a Duchy

If You Give a Duke a Duchy Runic Awakening (The Runic Series Book 1)

Runic Awakening (The Runic Series Book 1) The Lost Pathfinder

The Lost Pathfinder Ghosts, Gears, and Grimoires

Ghosts, Gears, and Grimoires Meg Xuemei X - Angel’s Mate (The Empress Of Mysth #6)

Meg Xuemei X - Angel’s Mate (The Empress Of Mysth #6) The Secret Of The Unicorn Queen - Sun Blind

The Secret Of The Unicorn Queen - Sun Blind Game Over

Game Over B018R79OOK EBOK

B018R79OOK EBOK OnlyIfItPleases

OnlyIfItPleases Gateway to Nifleheim

Gateway to Nifleheim SOF

SOF Crashing Into You

Crashing Into You Lessande D'Aramitz

Lessande D'Aramitz The Golden Circlet

The Golden Circlet B00H242ZGY EBOK

B00H242ZGY EBOK Barefoot Girls - Kindle

Barefoot Girls - Kindle Chronicles From The Future: The amazing story of Paul Amadeus Dienach

Chronicles From The Future: The amazing story of Paul Amadeus Dienach If you were my man

If you were my man Embrace

Embrace Hans Von Luck - Panzer Commander

Hans Von Luck - Panzer Commander AnythingForYou

AnythingForYou Fingers of Death—No, Doom!

Fingers of Death—No, Doom! How I Was Murdered By a Monster King (How I Was Murdered By a Fox Monster Book 2)

How I Was Murdered By a Monster King (How I Was Murdered By a Fox Monster Book 2) CaughtInTheTrap

CaughtInTheTrap something ends something begins sapkowski

something ends something begins sapkowski Detection by Gaslight

Detection by Gaslight Earth's Survivors Apocalypse

Earth's Survivors Apocalypse BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue001

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue001 B004M5HK0M EBOK

B004M5HK0M EBOK one twisted voice

one twisted voice John Shirley - Wetbones

John Shirley - Wetbones Not on the Passenger List

Not on the Passenger List The Alchemy Press Book of Urban Mythic 2

The Alchemy Press Book of Urban Mythic 2 A Changed Man (Altered Book 1)

A Changed Man (Altered Book 1) A Guide to the Birds of East Africa

A Guide to the Birds of East Africa KnockingonDemon'sDoor

KnockingonDemon'sDoor 15a The Prince and Betty

15a The Prince and Betty Unknown

Unknown You Are A Monster

You Are A Monster 9781618850058ForgottenSoulSinclair

9781618850058ForgottenSoulSinclair A Lesson in Taxonomy

A Lesson in Taxonomy Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present

Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present Michelle Woods - Becoming Raven's Man (Red Devils MC #7)

Michelle Woods - Becoming Raven's Man (Red Devils MC #7) Book 02, Growing Up

Book 02, Growing Up in1

in1 Zoey - Not Quite A Zombie

Zoey - Not Quite A Zombie Marion Zimmer Bradley's Sword and Sorceress XXIV

Marion Zimmer Bradley's Sword and Sorceress XXIV November 1930

November 1930 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole Evolve: Vampire Stories of the New Undead

Evolve: Vampire Stories of the New Undead Pieces of Olivia

Pieces of Olivia The Scandalous Son

The Scandalous Son In Red Rune Canyon

In Red Rune Canyon East-West

East-West Wolf2are

Wolf2are The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 3

The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 3 Death Watch

Death Watch Charles Willeford - New Hope For The Dead

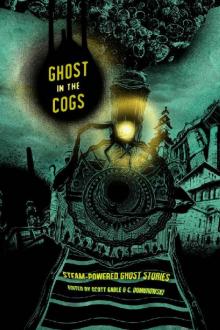

Charles Willeford - New Hope For The Dead Ghost in the Cogs: Steam-Powered Ghost Stories

Ghost in the Cogs: Steam-Powered Ghost Stories![[No data] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/no_data_preview.jpg) [No data]

[No data] B006ITK0AW EBOK

B006ITK0AW EBOK Pulp Fiction | The Ghost Riders Affair (July 1966)

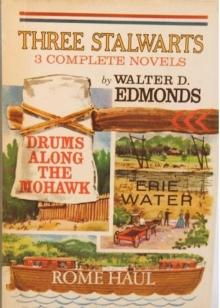

Pulp Fiction | The Ghost Riders Affair (July 1966) 3stalwarts

3stalwarts Classroom Demons

Classroom Demons Don't Tell Alfred

Don't Tell Alfred New Order: Urban Fantasy (Hidden Vampire Slayer Book 1)

New Order: Urban Fantasy (Hidden Vampire Slayer Book 1) Midnight at Mart’s

Midnight at Mart’s JEAPers Creepers

JEAPers Creepers 0597092001436358459 eveline vine

0597092001436358459 eveline vine Charles Willeford - Sideswipe

Charles Willeford - Sideswipe 2012-08-In the Event of My Untimely Demise

2012-08-In the Event of My Untimely Demise 05 William Tell Told Again

05 William Tell Told Again One Hot Night Old Port Nights, Book 1

One Hot Night Old Port Nights, Book 1 The Walkers from the Crypt

The Walkers from the Crypt The Box

The Box The Descendants (Evolution of Angels Book 2)

The Descendants (Evolution of Angels Book 2) Chapter 1

Chapter 1 B01N5EQ4R1 EBOK

B01N5EQ4R1 EBOK TexasKnightsBundle

TexasKnightsBundle Phoebe - Not Quite A Pheonix

Phoebe - Not Quite A Pheonix May 1931

May 1931 Stranded in Paradise

Stranded in Paradise Awaken

Awaken Butterfly Kisses (The Butterfly Chronicles #2)

Butterfly Kisses (The Butterfly Chronicles #2) No Game No Life Vol.7

No Game No Life Vol.7 bb-6565_deep_crotch_mother_curt_aldrich_

bb-6565_deep_crotch_mother_curt_aldrich_ Princess of Thorns

Princess of Thorns German Baking Today - German Baking Today

German Baking Today - German Baking Today Kylie Brant - What the Dead Know (The Mindhunters Book 8)

Kylie Brant - What the Dead Know (The Mindhunters Book 8) Melissa Schroeder - A Santini Takes the Fall (The Santinis Book #9)

Melissa Schroeder - A Santini Takes the Fall (The Santinis Book #9) Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon Oasis

Oasis The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 2

The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 2 Clare Kauter - Sled Head (Damned, Girl! Book 2)

Clare Kauter - Sled Head (Damned, Girl! Book 2) Do Sparrows Like Bach?: The Strange and Wonderful Things that Are Discovered When Scientists Break Free

Do Sparrows Like Bach?: The Strange and Wonderful Things that Are Discovered When Scientists Break Free The Silver Eagle

The Silver Eagle Soldier Up

Soldier Up Do Not Return To Sender

Do Not Return To Sender From This Moment On: The Sullivans, Book 2 (Contemporary Romance)

From This Moment On: The Sullivans, Book 2 (Contemporary Romance) Marina Adair - Need You for Keeps (St. Helena Vineyard #6)

Marina Adair - Need You for Keeps (St. Helena Vineyard #6) 02 A Prefect's Uncle

02 A Prefect's Uncle The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue008

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue008 Lily Knight - Hunt's Desire Vol. 1

Lily Knight - Hunt's Desire Vol. 1 RICHARD POWERS

RICHARD POWERS Another Part of the Wood

Another Part of the Wood Finding Me: Book 1: All I've Ever Wanted (A New Adult Romance Series)

Finding Me: Book 1: All I've Ever Wanted (A New Adult Romance Series) Blood Sunset

Blood Sunset Hanzai Japan: Fantastical, Futuristic Stories of Crime From and About Japan

Hanzai Japan: Fantastical, Futuristic Stories of Crime From and About Japan yame

yame X: The Hunt Begins

X: The Hunt Begins New Title 1

New Title 1 Borderlands 2

Borderlands 2 Snow, C.P. - George Passant (aka Strangers and Brothers).txt

Snow, C.P. - George Passant (aka Strangers and Brothers).txt Mother Bears

Mother Bears CONDITION BLACK MASTER

CONDITION BLACK MASTER 9781618850676UnchainedMelodyHunter

9781618850676UnchainedMelodyHunter Sexy to Go Volume 5

Sexy to Go Volume 5 Sexy to Go Volume 3

Sexy to Go Volume 3 9781618850607ForeverNightDayNC

9781618850607ForeverNightDayNC Shafted

Shafted Prodigal Sons

Prodigal Sons Daughters of Absence: Transforming a Legacy of Loss

Daughters of Absence: Transforming a Legacy of Loss B004V9FYIY EBOK

B004V9FYIY EBOK Sarah Curtis - Pursuing (Alluring Book 3)

Sarah Curtis - Pursuing (Alluring Book 3) LostFound_Azod

LostFound_Azod Pig Island

Pig Island Dangerous Women

Dangerous Women Annie Nicholas - Bootcamp of Misfits Wolves (Vanguard Elite Book 1)

Annie Nicholas - Bootcamp of Misfits Wolves (Vanguard Elite Book 1) Book 01, Coiling Dragon Ring

Book 01, Coiling Dragon Ring MENAGE: Triple Obsession (MMF Bisexual Menage Romance Collection) (New Adult Taboo Menage Romance Short Stories)

MENAGE: Triple Obsession (MMF Bisexual Menage Romance Collection) (New Adult Taboo Menage Romance Short Stories) Going Too Far

Going Too Far A Field Guide To Catching Crickets: ( a sexy second chance tearjerker romance )

A Field Guide To Catching Crickets: ( a sexy second chance tearjerker romance ) The Call of Destiny (The Return of Arthur Book 1)

The Call of Destiny (The Return of Arthur Book 1) Vanished

Vanished i 02b985df59d24adc

i 02b985df59d24adc Kacie's Surrender (Homeward Bound Book 1)

Kacie's Surrender (Homeward Bound Book 1) The End - Visions of Apocalypse

The End - Visions of Apocalypse Immersion (Magnetic Desires)

Immersion (Magnetic Desires) Borderlands

Borderlands The Ghosts of Broken Blades

The Ghosts of Broken Blades Alphas Gone Wild

Alphas Gone Wild Lord of Penance

Lord of Penance echristian-epub-ee8a4ba5-94c3-4982-ae55-299db4e26c11

echristian-epub-ee8a4ba5-94c3-4982-ae55-299db4e26c11 Sharon Karaa The Last Challenge (Northern Witches Series #1)

Sharon Karaa The Last Challenge (Northern Witches Series #1) Somebody to Love

Somebody to Love The Oxford Book of American Essays

The Oxford Book of American Essays The_ORDER_of_SHADDAI

The_ORDER_of_SHADDAI Love On A Forbidden Planet

Love On A Forbidden Planet 09 Not George Washington

09 Not George Washington RINGOFTRUTHEBOOK (1)

RINGOFTRUTHEBOOK (1) HEARTTHROB

HEARTTHROB Evolve Two: Vampire Stories of the Future Undead

Evolve Two: Vampire Stories of the Future Undead Eternal_Bliss

Eternal_Bliss Busted Flush

Busted Flush Shy...

Shy... The Fifth Woman

The Fifth Woman Forever My Home (The Aster Lake Series Book 1)

Forever My Home (The Aster Lake Series Book 1) ice man

ice man contamination 7 resistance con

contamination 7 resistance con Horror Books: The Lodge - (Adults, Paranormal, Ghost, Scary, Short Stories)

Horror Books: The Lodge - (Adults, Paranormal, Ghost, Scary, Short Stories) Wounded Birds (The Grayson Series Book 1)

Wounded Birds (The Grayson Series Book 1) When Love Calls

When Love Calls Beyond the Veil, Book 5 The Grey Wolves Series

Beyond the Veil, Book 5 The Grey Wolves Series Finger Lickin' Fifteen

Finger Lickin' Fifteen Daz 4 Zoe

Daz 4 Zoe When Our Worlds Fall Apart

When Our Worlds Fall Apart Tangled Up In Love

Tangled Up In Love Finding Love in a Dark World: A Steamy Post-Apocalyptic Romance

Finding Love in a Dark World: A Steamy Post-Apocalyptic Romance The Ironroot Deception

The Ironroot Deception One Stormy Night

One Stormy Night Third Reich Victorious

Third Reich Victorious Carol Marinelli - Bound To The Sheikh

Carol Marinelli - Bound To The Sheikh The Perfumer's Apprentice

The Perfumer's Apprentice True Ghost Stories: Real Short Tales of the Supernatural (The Real Paranormal Psychic Series)

True Ghost Stories: Real Short Tales of the Supernatural (The Real Paranormal Psychic Series) The Ex-Files

The Ex-Files CR!FAQVHAE2713SQDF4PGQ1SC7ZMJ68

CR!FAQVHAE2713SQDF4PGQ1SC7ZMJ68 Three for Dinner

Three for Dinner Waxwings

Waxwings Cheyenne McCray - Point Blank (Lawmen Book 4)

Cheyenne McCray - Point Blank (Lawmen Book 4) Document1

Document1 The Ugly Stepsister Strikes Back

The Ugly Stepsister Strikes Back Amy Sumida - Eye of Re (The Godhunter Book 17)

Amy Sumida - Eye of Re (The Godhunter Book 17) mywolfprotector

mywolfprotector Thrity Umrigar

Thrity Umrigar Pulp Fiction | The Vanishing Act Affair (June 1966)

Pulp Fiction | The Vanishing Act Affair (June 1966) Amy Sumida - Rain or Monkeyshine (Book 15 in The Godhunter Series)

Amy Sumida - Rain or Monkeyshine (Book 15 in The Godhunter Series) Moon's Sweet Poison

Moon's Sweet Poison The Lessons

The Lessons 9781618851307WitchsBrewShayNC

9781618851307WitchsBrewShayNC Linsey Hall - Stolen Fate (The Mythean Arcana #4)

Linsey Hall - Stolen Fate (The Mythean Arcana #4) 9781618854674DonovansBluesWaitsNC

9781618854674DonovansBluesWaitsNC August 1931

August 1931 Certainty

Certainty The Feng Shui Detective

The Feng Shui Detective Cider Brook

Cider Brook Lots of Love

Lots of Love![[Wild fang project] Garouden I pure fighting action novel Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/26/wild_fang_project_garouden_i_pure_fighting_action_novel_preview.jpg) [Wild fang project] Garouden I pure fighting action novel

[Wild fang project] Garouden I pure fighting action novel Atomic Swarm

Atomic Swarm The Dream of Perpetual Motion

The Dream of Perpetual Motion Our Family Trouble The Story of the Bell Witch of Tennessee

Our Family Trouble The Story of the Bell Witch of Tennessee Crystal Enchantment

Crystal Enchantment anightwithoutstarsfinal

anightwithoutstarsfinal Lone Star Vampires 4- Virgin Vampire Vixen

Lone Star Vampires 4- Virgin Vampire Vixen Selena Kitt - Hayden (Stepbrother Studs)

Selena Kitt - Hayden (Stepbrother Studs) Sidetracked

Sidetracked Books Burn Badly

Books Burn Badly Man in the Fedora

Man in the Fedora Honor Raconteur - Lost Mage (Advent Mage Cycle 06)

Honor Raconteur - Lost Mage (Advent Mage Cycle 06) Joy in the Morning

Joy in the Morning Faithful Servants

Faithful Servants Seducing Megan: Prossers Bay Series Novella

Seducing Megan: Prossers Bay Series Novella Perfect Imperfections

Perfect Imperfections B00BCLBHSA EBOK

B00BCLBHSA EBOK Serving Him: Sexy Stories of Submission

Serving Him: Sexy Stories of Submission Sylvie Sommerfield - Noah's Woman

Sylvie Sommerfield - Noah's Woman Light of a Distant Star

Light of a Distant Star Devil May Care

Devil May Care J.M. Sevilla - Summer Nights

J.M. Sevilla - Summer Nights Side Order of Love

Side Order of Love Jerilee Kaye - Intertwined

Jerilee Kaye - Intertwined Afraid Of A Gun and Other Stories

Afraid Of A Gun and Other Stories mark darrow and the stealer of

mark darrow and the stealer of The Eyes of the Rigger

The Eyes of the Rigger Something Wicked Anthology of Speculative Fiction, Volume Two

Something Wicked Anthology of Speculative Fiction, Volume Two SevenDeadlySinsSeries

SevenDeadlySinsSeries Gabriel's Rule

Gabriel's Rule Spider

Spider 9781618853073LyricsandLustLabelleNC

9781618853073LyricsandLustLabelleNC Vadalia - Not Quite A Vampire

Vadalia - Not Quite A Vampire Dogwood Hill (A Chesapeake Shores Novel - Book 12)

Dogwood Hill (A Chesapeake Shores Novel - Book 12) Dark Valley Destiny

Dark Valley Destiny Pulp Fiction | The Stone-Cold Dead in the Market Affair by John Oram

Pulp Fiction | The Stone-Cold Dead in the Market Affair by John Oram Layla Nash - A Valentine's Chase (City Shifters: the Pride)

Layla Nash - A Valentine's Chase (City Shifters: the Pride) 1400069106Secret

1400069106Secret The Sum of Love (Treasure Harbor Book 7)

The Sum of Love (Treasure Harbor Book 7) Demonhome (Champions of the Dawning Dragons Book 3)

Demonhome (Champions of the Dawning Dragons Book 3) Shadow Queen

Shadow Queen Pulp Fiction | The Dagger Affair by David McDaniel

Pulp Fiction | The Dagger Affair by David McDaniel Degree of Guilt

Degree of Guilt Granta 121: Best of Young Brazilian Novelists

Granta 121: Best of Young Brazilian Novelists HALLOWED_BE_THY_NAME

HALLOWED_BE_THY_NAME Oz Reimagined: New Tales from the Emerald City and Beyond

Oz Reimagined: New Tales from the Emerald City and Beyond Summer with the Millionaire

Summer with the Millionaire Border Crossing

Border Crossing Always Us (We Were Us Series Book 2)

Always Us (We Were Us Series Book 2) Book 03, Mountain Range of Magical Beasts

Book 03, Mountain Range of Magical Beasts My New Billionaire Stepbrother

My New Billionaire Stepbrother 08 The White Feather

08 The White Feather Single in the City

Single in the City 9781629270050-Text-for-ePub-rev

9781629270050-Text-for-ePub-rev![A Wodehouse Miscellany Articles and Stories(13 articles; When Papa Swore in Hindustani [1901]; Tom, Dick, and Harry [1905]; Jeeves Takes Charge [1916]; Disentangling Old Duggie) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/a_wodehouse_miscellany_articles_and_stories13_takes_charge_1916_disentangling_old_duggie_preview.jpg) A Wodehouse Miscellany Articles and Stories(13 articles; When Papa Swore in Hindustani [1901]; Tom, Dick, and Harry [1905]; Jeeves Takes Charge [1916]; Disentangling Old Duggie)

A Wodehouse Miscellany Articles and Stories(13 articles; When Papa Swore in Hindustani [1901]; Tom, Dick, and Harry [1905]; Jeeves Takes Charge [1916]; Disentangling Old Duggie) CR!93BHZ3MAHS4NVAVVWQG1QCZMZ0ZB

CR!93BHZ3MAHS4NVAVVWQG1QCZMZ0ZB Ladies’ Night

Ladies’ Night PINNACLE BOOKS NEW YORK

PINNACLE BOOKS NEW YORK Butterfly

Butterfly Fairy Tale Review

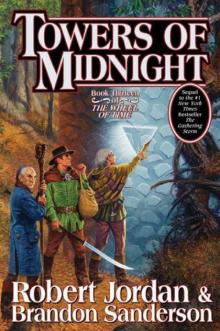

Fairy Tale Review Towers of Midnight by Robert Jordan and Robert Sanderson

Towers of Midnight by Robert Jordan and Robert Sanderson Pulp Fiction | The Pillars of Salt Affair (Dec. 1967)

Pulp Fiction | The Pillars of Salt Affair (Dec. 1967) EdgeOfHuman

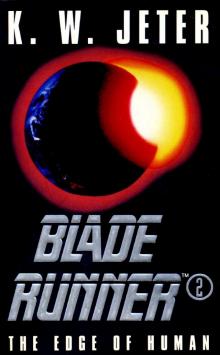

EdgeOfHuman Carter, Beth D. - Lawless Hearts (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Carter, Beth D. - Lawless Hearts (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Robert Goddard — Borrowed Time

Robert Goddard — Borrowed Time Gerry Bartlett - Rafe and the Redhead (Real Vampires)

Gerry Bartlett - Rafe and the Redhead (Real Vampires) In The Realm of Gods

In The Realm of Gods Shifter Romance Box Set

Shifter Romance Box Set B01M0OJOU7 EBOK

B01M0OJOU7 EBOK See Bride Run!

See Bride Run! AnotherKindofSummer

AnotherKindofSummer A Perfect Night

A Perfect Night Samantha Holt - Sinful Temptations (Cynfell Brothers Book 6)

Samantha Holt - Sinful Temptations (Cynfell Brothers Book 6) SECRETS Vol. 5

SECRETS Vol. 5 Sexy to Go Volume 2

Sexy to Go Volume 2 03 Tales of St.Austin's

03 Tales of St.Austin's French Decadent Tales (Oxford World's Classics)

French Decadent Tales (Oxford World's Classics) Phantasm Japan: Fantasies Light and Dark, From and About Japan

Phantasm Japan: Fantasies Light and Dark, From and About Japan 01 The Pothunters

01 The Pothunters Roxanne St. Claire - Barefoot With a Bad Boy (Barefoot Bay Undercover #3)

Roxanne St. Claire - Barefoot With a Bad Boy (Barefoot Bay Undercover #3) My Father's Tears and Other Stories

My Father's Tears and Other Stories Every Part of You Taunts Me

Every Part of You Taunts Me WorldLost- Week 1: An Infected Novel

WorldLost- Week 1: An Infected Novel July 1930

July 1930 Kennedy In Denver (In Denver Series Book 1)

Kennedy In Denver (In Denver Series Book 1) bw280

bw280 9781618854490WildChelceeNC

9781618854490WildChelceeNC Stargazer Maxima (Cosmic Justice League Book 1)

Stargazer Maxima (Cosmic Justice League Book 1) Complete Works of James Joyce

Complete Works of James Joyce The Collected Westerns of William MacLeod Raine: 21 Novels in One Volume

The Collected Westerns of William MacLeod Raine: 21 Novels in One Volume BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue003

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue003 ebooksclub.org Open Secrets Stories

ebooksclub.org Open Secrets Stories The Possibility of Us

The Possibility of Us Purple Haze (Blue Dream Book 2)

Purple Haze (Blue Dream Book 2) The Season of Passage

The Season of Passage The Onyx Talisman

The Onyx Talisman King of Kings

King of Kings After the Rain (The Twisted Fate Series Book 1)

After the Rain (The Twisted Fate Series Book 1) The Blessing

The Blessing Ann H

Ann H DeathOBTourist

DeathOBTourist Sword and Sorceress XXVII

Sword and Sorceress XXVII New Blood (The Blood Saga Book 2)

New Blood (The Blood Saga Book 2) GRANDMA'S ATTIC SERIES

GRANDMA'S ATTIC SERIES A Bad Day for Sorry

A Bad Day for Sorry 06 The Head of Kay's

06 The Head of Kay's Diehl, William - Show of Evil

Diehl, William - Show of Evil Two Pieces of Tarnished Silver

Two Pieces of Tarnished Silver The Fate of Falling Stars

The Fate of Falling Stars Behind the Pines (The Gass County Series Book 3)

Behind the Pines (The Gass County Series Book 3) Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell Love and a Blue-Eyed Cowboy

Love and a Blue-Eyed Cowboy The Swamp Warden

The Swamp Warden Fight With Me (Fight and Fall)

Fight With Me (Fight and Fall) Candy Girl

Candy Girl GODWALKER

GODWALKER Red Mandarin Dress

Red Mandarin Dress Oscar

Oscar After the Fire, A Still Small Voice

After the Fire, A Still Small Voice To Get To You

To Get To You Neruda and Vallejo: Selected Poems

Neruda and Vallejo: Selected Poems You Don't Have to be Good

You Don't Have to be Good Jane Vejjajiva

Jane Vejjajiva Phoenix Daniels- Beautiful Prey 3

Phoenix Daniels- Beautiful Prey 3 Michelle Woods - Animal Passions (Blue Bandits MC Book 2)

Michelle Woods - Animal Passions (Blue Bandits MC Book 2) WE

WE The Way of the Sword

The Way of the Sword Sarwat Chadda - Billi SanGreal 02 - Dark Goddess

Sarwat Chadda - Billi SanGreal 02 - Dark Goddess ChristmastoDieFor

ChristmastoDieFor Alphas Prefer Curves

Alphas Prefer Curves The Hot Pink Farmhouse

The Hot Pink Farmhouse The Cry of the Marwing

The Cry of the Marwing Love Lies

Love Lies The Scars of Saints

The Scars of Saints Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Penguin Classics)

Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Penguin Classics) THE COLD FIRE-

THE COLD FIRE- Imminent Danger (Adrenaline Highs)

Imminent Danger (Adrenaline Highs) BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue007

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue007 Cox, Suzanne - Unexpected Daughter

Cox, Suzanne - Unexpected Daughter Closer to the Heart (The Heart Trilogy Book 3)

Closer to the Heart (The Heart Trilogy Book 3) February 1931

February 1931 How To Write Magical Words: A Writer's Companion

How To Write Magical Words: A Writer's Companion Homeland Security (Defenders of Love Book 2)

Homeland Security (Defenders of Love Book 2) The_Chronicl-ir_to_the_King

The_Chronicl-ir_to_the_King The Project Gutenberg eBook of To Invade New York.... , by Irwin Lewis

The Project Gutenberg eBook of To Invade New York.... , by Irwin Lewis February 1930

February 1930 THE_REALM_SHIFT

THE_REALM_SHIFT Devi

Devi Wolf3are

Wolf3are Hearts Through Time

Hearts Through Time BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue005

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue005 A CRY FROM THE DEEP

A CRY FROM THE DEEP Without Prejudice

Without Prejudice The Daughter's Return

The Daughter's Return Amy Sumida - Light as a Feather (Book 14 in The Godhunter Series)

Amy Sumida - Light as a Feather (Book 14 in The Godhunter Series) Third World War

Third World War The curse of Kalaan

The curse of Kalaan Crash Lights and Sirens, Book 1

Crash Lights and Sirens, Book 1 Debra Webb - Depraved (Faces of Evil Book 10)

Debra Webb - Depraved (Faces of Evil Book 10) Amy Sumida - Perchance To Die (The Godhunter Book 12)

Amy Sumida - Perchance To Die (The Godhunter Book 12) The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz by Russell Hoban(1973)

The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz by Russell Hoban(1973) Rough Around the Edges Meets Refined (Meet Your Match, book 2)

Rough Around the Edges Meets Refined (Meet Your Match, book 2) A Soul's Sacrifice (Voodoo Revival Series Book 1)

A Soul's Sacrifice (Voodoo Revival Series Book 1) Charles Willeford - Way We Die Now

Charles Willeford - Way We Die Now Type here book author - Type here book title

Type here book author - Type here book title 2012-09-Shattered Steel

2012-09-Shattered Steel With Strings Attached

With Strings Attached 9781618853462BlindEcstasyHoltNC

9781618853462BlindEcstasyHoltNC Girl Friday

Girl Friday An Unacceptable Death - Barbara Seranella

An Unacceptable Death - Barbara Seranella Hidden Realms

Hidden Realms Last Night Another Soldier

Last Night Another Soldier The Worst Witch to the Rescue

The Worst Witch to the Rescue Immortal of Darkness

Immortal of Darkness the eye of the tiger

the eye of the tiger The Last Illusion

The Last Illusion June 1931

June 1931 Taming Her Italian Boss

Taming Her Italian Boss Once Bitten - Clare Willis

Once Bitten - Clare Willis 9781618852014TheSpaceCougarsCadetPierce

9781618852014TheSpaceCougarsCadetPierce Pulp Fiction | The Invisibility Affair by Thomas Stratton

Pulp Fiction | The Invisibility Affair by Thomas Stratton TrustMe

TrustMe White Is for Witching

White Is for Witching May 1930

May 1930 The Girl of Diamonds and Rust (The Half Shell Series Book 3)

The Girl of Diamonds and Rust (The Half Shell Series Book 3) DropZone

DropZone 29 Three Men and a Maid

29 Three Men and a Maid bc-1010_mother_in_bondage_paul_gable_

bc-1010_mother_in_bondage_paul_gable_ Complicated Matters

Complicated Matters Untitled0

Untitled0 changing-places-david-lodge

changing-places-david-lodge The Winter House

The Winter House The Alchemy Press Book of Urban Mythic

The Alchemy Press Book of Urban Mythic HORRORS! #2 More Rarely Reprinted Classic Terror Tales

HORRORS! #2 More Rarely Reprinted Classic Terror Tales Best European Fiction 2013

Best European Fiction 2013 Earthquake

Earthquake The Secret of the Rose and Glove

The Secret of the Rose and Glove What to Do When Someone Dies

What to Do When Someone Dies Amy Sumida - Tracing Thunder (The Godhunter Series Book 13)

Amy Sumida - Tracing Thunder (The Godhunter Series Book 13) True Ghost Stories: Real Accounts of Death and Dying, Grief and Bereavement, Soulmates and Heaven, Near Death Experiences, and Other Paranormal Mysteries (The Supernatural Book Series: Volume 2)

True Ghost Stories: Real Accounts of Death and Dying, Grief and Bereavement, Soulmates and Heaven, Near Death Experiences, and Other Paranormal Mysteries (The Supernatural Book Series: Volume 2) Manage Me (Taven's Circus Book 1)

Manage Me (Taven's Circus Book 1) 9781618850638IfOnlyYouKnewBergman

9781618850638IfOnlyYouKnewBergman Islamic States of America (Soldier Up Book 2)

Islamic States of America (Soldier Up Book 2) book

book Another World

Another World Amy Sumida - Out of the Darkness (The Godhunter Book 11)

Amy Sumida - Out of the Darkness (The Godhunter Book 11) The Rainbow Pool

The Rainbow Pool The Pantheon: From Antiquity to the Present

The Pantheon: From Antiquity to the Present 2012-12-Thieves Vinegar

2012-12-Thieves Vinegar in0

in0 Wolf's Bane: Book Three of the Demimonde

Wolf's Bane: Book Three of the Demimonde 11 The Swoop

11 The Swoop Spud

Spud Urban Legend

Urban Legend 01

01 Taking Whatever He Wants: The Cline Brothers of Colorado

Taking Whatever He Wants: The Cline Brothers of Colorado 0968348001325302640 brenda huber shadows

0968348001325302640 brenda huber shadows Tales of the German Imagination from the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann (Penguin Classics)

Tales of the German Imagination from the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann (Penguin Classics) AccidentalVoyeur

AccidentalVoyeur Dark Delicacies II: Fear; More Original Tales of Terror and the Macabre by the World's Greatest Horror Writers

Dark Delicacies II: Fear; More Original Tales of Terror and the Macabre by the World's Greatest Horror Writers A. Zavarelli - Stutter (Bleeding Hearts Book 2)

A. Zavarelli - Stutter (Bleeding Hearts Book 2) Oklahoma kiss

Oklahoma kiss Born To Be Wild

Born To Be Wild Catching Haley (Falling for Bentley Book 2)

Catching Haley (Falling for Bentley Book 2) BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue002

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue002 The Seventh Execution

The Seventh Execution Simply Beautiful

Simply Beautiful Adaptation Part Two

Adaptation Part Two The Way of the Dragon

The Way of the Dragon Aminadab 0803213131

Aminadab 0803213131 9781622661848 EPUB

9781622661848 EPUB Pulp Fiction | The Cat and Mouse Affair (August 1966)

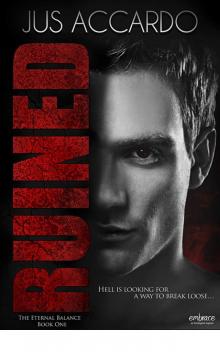

Pulp Fiction | The Cat and Mouse Affair (August 1966) The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard Original)

The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard Original) The Thackery T Lambshead Pocket Guide To Eccentric & Discredited Diseases

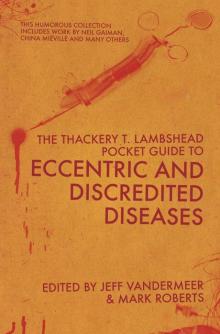

The Thackery T Lambshead Pocket Guide To Eccentric & Discredited Diseases 9781618853011NoHoldsBarredChelcee

9781618853011NoHoldsBarredChelcee Ruth Ann Scott - Alien Romance - Saved By An Alien

Ruth Ann Scott - Alien Romance - Saved By An Alien Borderlands 5

Borderlands 5 Susan Hatler - Just One Kiss (Kissed by the Bay Book 3)

Susan Hatler - Just One Kiss (Kissed by the Bay Book 3) Stephanie Thomas - Lucidity

Stephanie Thomas - Lucidity Whisper of Leaves

Whisper of Leaves Charity's Warrior

Charity's Warrior Nine Months to Change His Life

Nine Months to Change His Life Surrendered: A Collection of Five Works

Surrendered: A Collection of Five Works book_template2.qxd

book_template2.qxd Guardian

Guardian I Dream of Yellow Kites: What if it was all just a nightmare?

I Dream of Yellow Kites: What if it was all just a nightmare? Delilah Devlin - Sm{B}itten (Night Fall #1)

Delilah Devlin - Sm{B}itten (Night Fall #1) BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue004

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue004 Body Heat

Body Heat J.Rihards - An Agitated Gentleman (The Submission Series #2)

J.Rihards - An Agitated Gentleman (The Submission Series #2) The Forsaken Rose: (Clean Young Adult, Fantasy Romance) (Rose Belmont Series)

The Forsaken Rose: (Clean Young Adult, Fantasy Romance) (Rose Belmont Series) Johnny Dash and the Doral Flower (Johhny Dash Series Book 1)

Johnny Dash and the Doral Flower (Johhny Dash Series Book 1) BeneathCeaselessSkies_Issue011

BeneathCeaselessSkies_Issue011 Change of Heart by Jack Allen

Change of Heart by Jack Allen Arnica Butler - Well-Constructed Affairs

Arnica Butler - Well-Constructed Affairs Marie Force - And I Love You (Green Mountain #4)

Marie Force - And I Love You (Green Mountain #4) The Orphic Hymns

The Orphic Hymns Perfect Personality Profiles

Perfect Personality Profiles William F. Nolan - Logan's Run Trilogy (v4.1)

William F. Nolan - Logan's Run Trilogy (v4.1) o ca77aeec6e4cf556

o ca77aeec6e4cf556 HisHumanCow

HisHumanCow BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue010

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue010 Tampa Black: Part !

Tampa Black: Part ! Ruby's Song (Love in the Sierras Book 3)

Ruby's Song (Love in the Sierras Book 3) Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense

Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense The Bonedust Dolls

The Bonedust Dolls GodOfWar05152014aLLROMANCE

GodOfWar05152014aLLROMANCE October 1930

October 1930 Bright Fires Burn Fastest

Bright Fires Burn Fastest March 1931

March 1931 Pulp Fiction | The Finger in the Sky Affair by Peter Leslie

Pulp Fiction | The Finger in the Sky Affair by Peter Leslie Adien: The Sons Of The Apocalypse MC

Adien: The Sons Of The Apocalypse MC The Mao Case

The Mao Case Microsoft Word - Documento1

Microsoft Word - Documento1 Ghostwritten

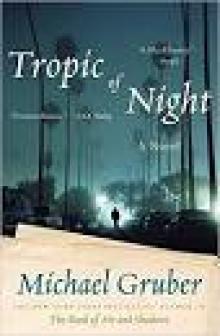

Ghostwritten Tropic of Night

Tropic of Night I Remember You (An Erotic Romance) - Isis Cole

I Remember You (An Erotic Romance) - Isis Cole StealingFireCalibre

StealingFireCalibre B00HSFFI1Q EBOK

B00HSFFI1Q EBOK Her Love Lost (Love Shattered Series Book 1)

Her Love Lost (Love Shattered Series Book 1) storm

storm Can’t Never Tell

Can’t Never Tell 4221 words

4221 words dontjudge06242014aRe

dontjudge06242014aRe My Lord Beaumont

My Lord Beaumont Gagliano,Anthony - Straits of Fortune.wps

Gagliano,Anthony - Straits of Fortune.wps DreamDatewiththeMillionaire

DreamDatewiththeMillionaire i de1359f7e9a78273

i de1359f7e9a78273 The Blind Side of the Heart

The Blind Side of the Heart Pleasure 2035

Pleasure 2035![Bobby Hutchinson - [Emergency 01] - Side Effects (HSR 723).htm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/bobby_hutchinson_-_emergency_01_-_side_effects_hsr_723_htm_preview.jpg) Bobby Hutchinson - [Emergency 01] - Side Effects (HSR 723).htm

Bobby Hutchinson - [Emergency 01] - Side Effects (HSR 723).htm The Unprintable Big Clock Chronicle

The Unprintable Big Clock Chronicle index

index Harari, Yuval Noah - Sapiens, A - Sapiens, A Brief History Of Hum

Harari, Yuval Noah - Sapiens, A - Sapiens, A Brief History Of Hum Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History

Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History Tainaron - Mail from another city

Tainaron - Mail from another city Porno

Porno Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Highland Shifters: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Highland Shifters: A Paranormal Romance Boxed Set Diary of a Vampeen: Vamp Yourself for War

Diary of a Vampeen: Vamp Yourself for War 12 Mike

12 Mike Sing to Me

Sing to Me B001GAQ55C_EBOK.prc

B001GAQ55C_EBOK.prc 22 The Man With Two Left Feet

22 The Man With Two Left Feet Serpent Moon

Serpent Moon The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 4

The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 4 9781618850034TroubleHunter

9781618850034TroubleHunter Dark Wood: Legends of the Guardians

Dark Wood: Legends of the Guardians Abduction Revelation II: Truth Be Told (The Comeback Kid)

Abduction Revelation II: Truth Be Told (The Comeback Kid) Pulp Fiction | The Hollow Crown Affair by David McDaniel

Pulp Fiction | The Hollow Crown Affair by David McDaniel Black Corner

Black Corner Hawkmoon (The Hawkmoon Chronicles)

Hawkmoon (The Hawkmoon Chronicles) 2012-11-Killing Time

2012-11-Killing Time Blood and Money

Blood and Money Pulp Fiction | The Synthetic Storm Affair (May 1967)

Pulp Fiction | The Synthetic Storm Affair (May 1967) Trespass

Trespass The Barrier: The Teorran of Time: Teen Fantasy Action Adventure Novel

The Barrier: The Teorran of Time: Teen Fantasy Action Adventure Novel Quarterback Sneak

Quarterback Sneak Adaptation Part One

Adaptation Part One amonthwithpub

amonthwithpub Waltz This Way

Waltz This Way BOH 8-21-07 (00178434).DOC

BOH 8-21-07 (00178434).DOC Helen Smith - Beyond Belief (Emily Castles #4)

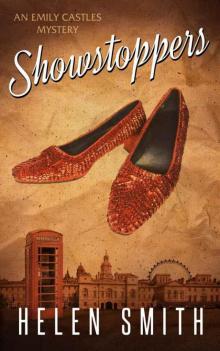

Helen Smith - Beyond Belief (Emily Castles #4) tmp0

tmp0 BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue009

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue009![The Politeness of Princes (The Politeness of Princes [1905]; Shields' and the Cricket Cup [1905]; An International Affair [1905]; The Guardian [1908]; A Corner in Lines [1905]; The Autograph Hunte Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/the_politeness_of_princes_the_politeness_of_pr_a_corner_in_lines_1905_the_autograph_hunte_preview.jpg) The Politeness of Princes (The Politeness of Princes [1905]; Shields' and the Cricket Cup [1905]; An International Affair [1905]; The Guardian [1908]; A Corner in Lines [1905]; The Autograph Hunte

The Politeness of Princes (The Politeness of Princes [1905]; Shields' and the Cricket Cup [1905]; An International Affair [1905]; The Guardian [1908]; A Corner in Lines [1905]; The Autograph Hunte Do or Die Reluctant Heroes

Do or Die Reluctant Heroes January 1931

January 1931 Susan Meissner - Why the Sky Is Blue

Susan Meissner - Why the Sky Is Blue B005H8M8UA EBOK

B005H8M8UA EBOK cause to run an avery black my

cause to run an avery black my B00N1384BU EBOK

B00N1384BU EBOK Severance Lost (Fractal Forsaken Series Book 1)

Severance Lost (Fractal Forsaken Series Book 1) Thrity Umrigar - First Darling of the Morning (mobi)

Thrity Umrigar - First Darling of the Morning (mobi) Her First Fisting

Her First Fisting Sophia Hampton - Withdrawal (Satan's Cubs Motorcycle Club Book 2)

Sophia Hampton - Withdrawal (Satan's Cubs Motorcycle Club Book 2) The Best Science Fiction of the Year: 1

The Best Science Fiction of the Year: 1 The Juggler And His Rose

The Juggler And His Rose Marion Zimmer Bradley's Sword and Sorceress XXVI

Marion Zimmer Bradley's Sword and Sorceress XXVI Love Lust

Love Lust PIECES OF LAUGHTER AND FUN

PIECES OF LAUGHTER AND FUN B00S79KYL6 EBOK

B00S79KYL6 EBOK World's Funniest Jokes (Volume I): Huge Collection of mainly dirty jokes, puns and humor for adults

World's Funniest Jokes (Volume I): Huge Collection of mainly dirty jokes, puns and humor for adults On killing

On killing The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction 1909-1959

The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction 1909-1959 Retaliation (The Assassins Book 1)

Retaliation (The Assassins Book 1) Enduring Love

Enduring Love B00F9G4R1S EBOK

B00F9G4R1S EBOK 9781618850478TwoForThePriceOfOneSullivan

9781618850478TwoForThePriceOfOneSullivan Moon Bound (Glorious Darkness Book 1)

Moon Bound (Glorious Darkness Book 1) A Silence in the Heavens

A Silence in the Heavens Rogue Oracle

Rogue Oracle Guns of Alkenstar

Guns of Alkenstar CourtesanTales Masterfile

CourtesanTales Masterfile Orders from Berlin

Orders from Berlin The Perfect Match

The Perfect Match Thea Frost - What His Darkness Reveals 04

Thea Frost - What His Darkness Reveals 04 September 1930

September 1930 Portia Moore - He Lived Next Door

Portia Moore - He Lived Next Door Pulp Fiction | The Vampire Affair by David McDaniel

Pulp Fiction | The Vampire Affair by David McDaniel Committed: An Erotic Valentine's Tale

Committed: An Erotic Valentine's Tale![Death At The Excelsior (Death at the Excelsior [1914]; Misunderstood [1910]; The Best Sauce [1911]; Jeeves and the Chump Cyril [1918]; Jeeves in the Springtime [1921]; Concealed Art [1915]; The Te Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/death_at_the_excelsior_death_at_the_excelsior_springtime_1921_concealed_art_1915_the_te_preview.jpg) Death At The Excelsior (Death at the Excelsior [1914]; Misunderstood [1910]; The Best Sauce [1911]; Jeeves and the Chump Cyril [1918]; Jeeves in the Springtime [1921]; Concealed Art [1915]; The Te

Death At The Excelsior (Death at the Excelsior [1914]; Misunderstood [1910]; The Best Sauce [1911]; Jeeves and the Chump Cyril [1918]; Jeeves in the Springtime [1921]; Concealed Art [1915]; The Te Selena Kitt - Gavin (Stepbrother Studs)

Selena Kitt - Gavin (Stepbrother Studs) Tiredness Kills - A Zombie Tale

Tiredness Kills - A Zombie Tale Shifting

Shifting Loser's Town

Loser's Town Thalia Lake - Choosey Lovers

Thalia Lake - Choosey Lovers The Savage Altar

The Savage Altar German Cooking Today

German Cooking Today The Touch of Love

The Touch of Love A Passage to Absalom

A Passage to Absalom A Beautiful Fate

A Beautiful Fate B071NZPNXN EBOK

B071NZPNXN EBOK Purveyors and Acquirers (The Phosfire Journeys Book 1)

Purveyors and Acquirers (The Phosfire Journeys Book 1) The Way You Love Me

The Way You Love Me Burned

Burned Microsoft Word - Book 12 FINAL

Microsoft Word - Book 12 FINAL Microsoft Word - TheEx-FactorFinal.docx

Microsoft Word - TheEx-FactorFinal.docx Amazing Stories 88th Anniversary Issue: Amazing Stories April 2014

Amazing Stories 88th Anniversary Issue: Amazing Stories April 2014 BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue006

BeneathCeaselessSkies Issue006 Charlene Hartnady - Stolen by the Alpha Wolf 3# (Determined Theft)

Charlene Hartnady - Stolen by the Alpha Wolf 3# (Determined Theft) UNTOUCHABLE

UNTOUCHABLE Family Storms

Family Storms Clean Romance: Loves of Tomorrow (Contemporary New Adult and College Amish Western Culture Romance) (Urban Power of Love Billionaire Western Collection Time Travel Short Stories)

Clean Romance: Loves of Tomorrow (Contemporary New Adult and College Amish Western Culture Romance) (Urban Power of Love Billionaire Western Collection Time Travel Short Stories) Pulp Fiction | The Goliath Affair (December 1966)

Pulp Fiction | The Goliath Affair (December 1966) Love and Punishment

Love and Punishment Won't Back Down: Won't Back Down

Won't Back Down: Won't Back Down von Willegen, Therése - Tainted Love (Siren Publishing Classic)

von Willegen, Therése - Tainted Love (Siren Publishing Classic) Broken

Broken The Fighter's Girl

The Fighter's Girl Watching You: KJ Elite Inc.

Watching You: KJ Elite Inc. J.A. Pierre - A New Dawn: From Rich Housewife to Suddenly Single

J.A. Pierre - A New Dawn: From Rich Housewife to Suddenly Single 14 Psmith in the City

14 Psmith in the City i 7d341843b82569de

i 7d341843b82569de Truly, Madly

Truly, Madly Noble Sacrifice

Noble Sacrifice Red Solstice (Alfheim Book 1)

Red Solstice (Alfheim Book 1) Volume 3: Ghost Stories from Texas (Joe Kwon's True Ghost Stories from Around the World)

Volume 3: Ghost Stories from Texas (Joe Kwon's True Ghost Stories from Around the World) HORRORS!: Rarely-Reprinted Classic Terror Tales

HORRORS!: Rarely-Reprinted Classic Terror Tales TheNine-MonthBride

TheNine-MonthBride Starfire

Starfire Loving Liza Jane

Loving Liza Jane Spring Fires

Spring Fires The Secret Friend

The Secret Friend Last Witness

Last Witness B00OPGSMHI EBOK

B00OPGSMHI EBOK KnightRiderLegacy

KnightRiderLegacy A Tale of Fur and Flesh

A Tale of Fur and Flesh Helen Smith - Real Elves: A Christmas Story (Emily Castles Mysteries #5)

Helen Smith - Real Elves: A Christmas Story (Emily Castles Mysteries #5) A.J. Bennett - Hired Gun #3 (The Sicarii)

A.J. Bennett - Hired Gun #3 (The Sicarii) Red Christmas

Red Christmas The Way Home (Lights of Peril)

The Way Home (Lights of Peril) Ever, Dirk: The Bogarde Letters

Ever, Dirk: The Bogarde Letters The Railway Detective

The Railway Detective Free Fall

Free Fall The Amateur Marriage

The Amateur Marriage Amy Sumida - Blood Bound (Book 16 in The Godhunter Series)

Amy Sumida - Blood Bound (Book 16 in The Godhunter Series) April 1931

April 1931 Temporally Out of Order

Temporally Out of Order HALLOWED_GROUND

HALLOWED_GROUND AJAYA I -- Roll of the Dice

AJAYA I -- Roll of the Dice Open File

Open File Addiction (Magnetic Desires Book 2)

Addiction (Magnetic Desires Book 2) Crybbe (AKA Curfew)

Crybbe (AKA Curfew) B00I8BCQ6O EBOK

B00I8BCQ6O EBOK tameallrom

tameallrom i beae453328863969

i beae453328863969 Hecate's Own: Heart's Desire, Book 2

Hecate's Own: Heart's Desire, Book 2 A Life In Blood (Chronicles of The Order Book 1)

A Life In Blood (Chronicles of The Order Book 1) The Commitment

The Commitment The Mighty First, Episode 1: Special Edition

The Mighty First, Episode 1: Special Edition Names My Sisters Call Me

Names My Sisters Call Me Sharon Karaa - A Familiar Problem (Northern Witches #2)

Sharon Karaa - A Familiar Problem (Northern Witches #2) August 1930

August 1930 The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 1

The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 1 Alexx Andria - A Christmas Promise

Alexx Andria - A Christmas Promise Bear of Interest

Bear of Interest i 5f46cfb4d10d4d86

i 5f46cfb4d10d4d86 IT

IT Tombstoning

Tombstoning Pulp Fiction | The Howling Teenagers Affair (February 1966)

Pulp Fiction | The Howling Teenagers Affair (February 1966) The Man From Beijing

The Man From Beijing So Paddy got up - an Arsenal anthology

So Paddy got up - an Arsenal anthology A Book of Mediterranean Food

A Book of Mediterranean Food Science Fiction Fantasies: Tales and Origins

Science Fiction Fantasies: Tales and Origins Lightning Rod Faces the Cyclops Queen

Lightning Rod Faces the Cyclops Queen Letting Go (A Mitchell Family Series)

Letting Go (A Mitchell Family Series) The Memory Game

The Memory Game Mandy M. Roth - Magic Under Fire (Over a Dozen Tales of Urban Fantasy)

Mandy M. Roth - Magic Under Fire (Over a Dozen Tales of Urban Fantasy) KD Robichaux- Wish he was you (The Blogger Diaries Trilogy Book 2)

KD Robichaux- Wish he was you (The Blogger Diaries Trilogy Book 2) B018YDIXDK EBOK

B018YDIXDK EBOK Julia Mills - Her Dragon's Heart (Dragon Guard Series Book 8)

Julia Mills - Her Dragon's Heart (Dragon Guard Series Book 8) Number9Dream

Number9Dream B00ICVKWMK EBOK

B00ICVKWMK EBOK The_Chronicl-_Rise_of_Lucin

The_Chronicl-_Rise_of_Lucin Harcourte Vampyre Society 02 Dangerous Choices

Harcourte Vampyre Society 02 Dangerous Choices Julian, by Gore Vidal

Julian, by Gore Vidal Amazing Stories 88th Anniversary Issue

Amazing Stories 88th Anniversary Issue Great Russian Short Stories

Great Russian Short Stories Dizzy

Dizzy The Men of CLE-FD updated

The Men of CLE-FD updated Victoria Connelly - The Rose Girl

Victoria Connelly - The Rose Girl Nine One One

Nine One One Borderlands 4

Borderlands 4 Change of Fate (The Briar Creek Vampires Series #4)

Change of Fate (The Briar Creek Vampires Series #4) The Treasure of Far Thallai

The Treasure of Far Thallai Dark Whispers Sheridan and Cain 2009

Dark Whispers Sheridan and Cain 2009 Charissa Dufour - Misguided Allies (The Void Series Book 2)

Charissa Dufour - Misguided Allies (The Void Series Book 2) Complete Works of J. M. Barrie

Complete Works of J. M. Barrie With Our Dying Breath

With Our Dying Breath Harcourte Vampyre Society 01 Dangerous Revelations

Harcourte Vampyre Society 01 Dangerous Revelations BootyARe05202014

BootyARe05202014